Urban-Rural

Divide Jharkhand’s political landscape illustrates the complexities of a state grappling with rapid urbanisation, stark rural realities, and growing communal tensions.

His commitment, pre-occupation, and whole-hearted dedication to the cause of developing agriculture, improving the condition of peasantry, and addressing the vexatious issue of land reforms was evident through these years.

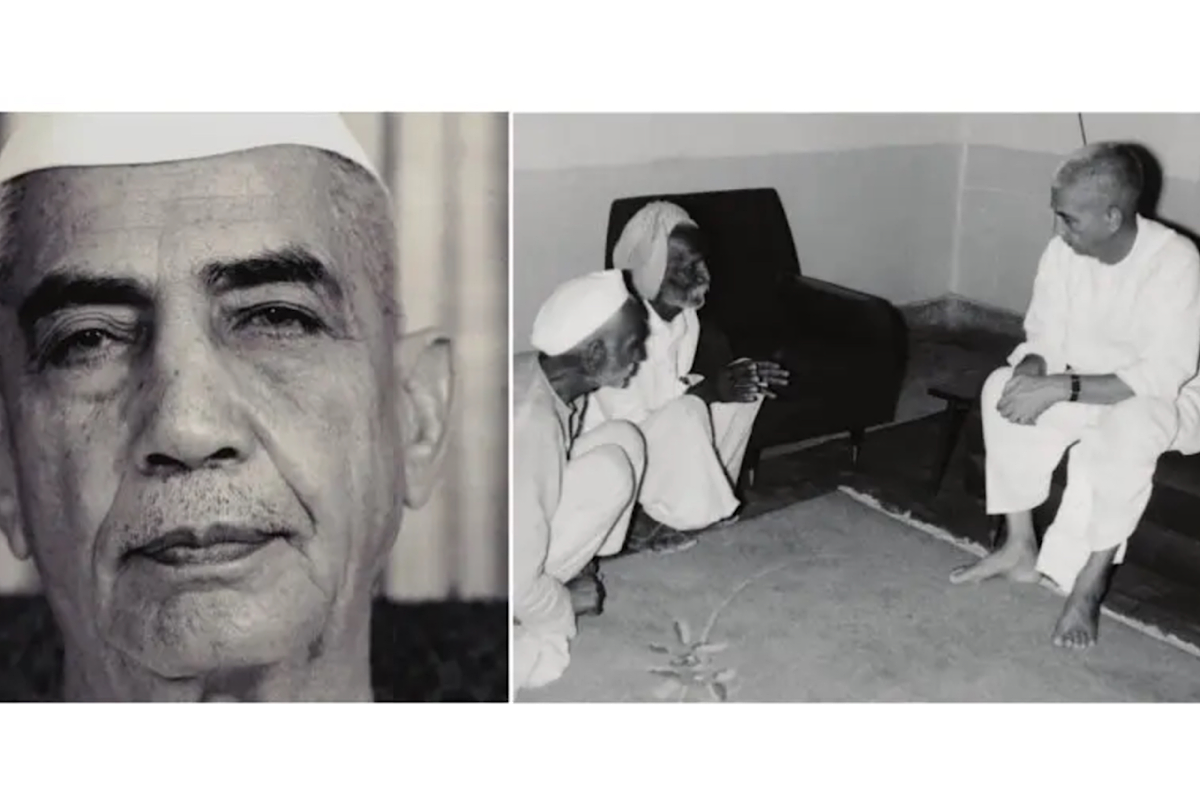

(Photos: PIB, CCS archives)

It was 21 March 1947 and Chaudhary Charan Singh had been discharging his duties as Parliamentary Secretary (or junior minister) in the Congress Ministry of the United Provinces since March 1946. He had been elected for the second time to the United Provinces Legislative Assembly from Meerut District (south-west).

His commitment, pre-occupation, and whole-hearted dedication to the cause of developing agriculture, improving the condition of peasantry, and addressing the vexatious issue of land reforms was evident through these years. If today’s generation could understand and empathise with the Bharat Ratna recipient of 2024, the article Charan Singh wrote titled ‘Why 60 per cent services should be reserved for sons of cultivators?’ would suffice.

“According to the Census of 1931,” wrote Charan Singh, utilizing his knowledge of history and law, “persons or earners who are engaged in cultivation of land form the largest bulk of the total earners of our province, viz, 57.75 per cent. When agricultural labourers are included, the figure swells to 75.5 per cent.” He was referring to tenants, small land-owners, and labourers, aware that occupational statistics were not collected in the Census of 1941 too. “It is the agriculturists, therefore, who are entitled to be called the people – the masses ~ of United Provinces,” declared Charan Singh, and the words leap out of the archival pages, almost as a clarion call. He said, “All the departments of the Government have been created with a view to serve the interests of the people.

Advertisement

Constituting as they do an overwhelming percentage of the population, one would expect that the Government services is the United Provinces would be manned largely by the sons of agriculturists or that at any rate their number in the services would somewhat nearly reflect their strength in the entire populace. But that is far from the case; a census of Government servants, according to the profession of their parents or guardians, is not available, but it can be asserted without fear of contradiction that their proportion excluding the services that are either risky, or are very poorly paid, and does not in any way exceed ten per cent. It is submitted that this state of things has to be radically altered.”

The magisterial tone of this memorandum, choice of words and clarity in his thought is not only remarkable but distinctly revolutionary. “In our country the classes whose scions dominate the public services area are either those which have been ‘raised to unexampled prominence and importance’ by the Britisher,” he said without fear, and pointed out it is the class of money-lenders, big zamindars and taluqdars, contractors and traders who have exploited the masses in all kinds of manner during the last 200 years.

Being in subordinate cooperation with foreigners, he wrote, “the interests and views of these classes on the whole are, therefore, manifestly opposed to those of the masses.” Revisiting Charan Singh’s thoughts that have universal appeal, and relevance till date, is to confront his deep understanding of the ‘social philosophy’ of non-agricultural urban classes vis-à-vis those belonging to agricultural rural classes.

He quoted a memorandum submitted to the Statutory Commission of Punjab which stated that “an immense cleavage exists in India between the trading classes in the cities and towns on the one hand, and the agricultural classes on the other.” The urban middle class, wrote Charan Singh, is akin to and includes the money-lending class, has no sympathy with agricultural classes whatsoever and that the interests of the two classes are diametrically opposed to one another. “The urban middle class, with the academic education they have received, look down upon agriculturists as being only good enough to plough land, produce food, supply the revenues, act as cannon fodder and to be exploited in every way conceivable.”

He acknowledged that though the language of the memorandum may sound a bit too harsh and blunt to many an ear; “but there is no gainsaying the fact that the city people act superior towards the peasant.” Having acquired degrees in science, history and law, Charan Singh was in sync with global ideas and ideologies through the 1920s and 1930s. In the memorandum he quoted the AustroHungarian philosopher-politician Richard Nikolaus Eijiro, Count of Coudenhove-Kalergi, who had written on European integration.

In his book, ‘Totalitarian State against Man’, the Count explained how agriculture produces a different kind of citizen, an attitude of mind and a way of life that is distinctly different from any other occupation: “The peasant lives in nature, with nature, and by nature, in symbiosis with animals and plants. For this reason, his picture of the world is fundamentally different from that of the townsman remote from nature, who spends his days among all kinds of machinery and often himself becomes a semi-machine.

The peasant has the slow tempo of the seasons and not the quick tempo of motor cars. His attitude towards the world and to things is organic and not mechanical.” In India, town-bred people who had nothing to do with agriculture contemptuously called the poor peasant a dehati, ganwar or dahgani, just as the European used to call them ‘natives’ or ‘niggers’. Charan Singh quoted his senior, the Hon’ble Sampurnanand, Education Minister of United Provinces who said, “Judges and legislators need not be deliberately unfair; being human, they would find it almost impossible to transcend the limitations imposed upon them by their class affiliations and group interests.”

Regarding law courts and judicial officers, Charan Singh was unsparing. His words ring with candour and fearlessness, when he pointed to the attitude, behaviour, and alliance of officers towards their own classes. “Given the same set of circumstances in a lawsuit, the reaction of a judge from a money-lending or taluqdar family differs greatly from that of a judge belonging to an agriculturist family…” He quoted from a British legal journal: “It is increasingly recognized that if justices are to do their work satisfactorily, they must have not only a working knowledge of the law they administer, but also a realization of the difficulties and problems of the people whose cases they try. It is said that a bench of justices from an agricultural district would fail to understand the conditions prevailing in a mining town, or in an industrial centre, and that equally the townsmen would fail to appreciate the problems of an agricultural community.”

In the Punjab Legislative Assembly, debates on the Restitution of Mortgaged Lands Bills and the Agricultural Marketing Bill had been heated during those years. Congress Party members, Charan Singh pointed out, refused to support the Bills despite Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s specific instructions. He felt that their urban and non-agricultural interests were overpowering and “I leave it to the reader to guess the reasons for their refusal. When such is the conduct of people who claim to be public workers, who call themselves Congressmen and this in an age when our leaders have set their hearts on vivifying the villages and when establishment of the ‘Peasants and Workers Raj’ is the avowed aim of all our political work, what shall we expect from ordinary people that usually secure the jobs in the various departments, who are neither public workers nor Congressmen and whose one avowed aim in life is the aggrandizement of self and the conscious or unconscious furtherance of the interest of their group?” Charan Singh goes on to quote Karl Marx who had “propagated the view that the class which controls the State will always use its power in its own interest. Though this view may be unjustified as an absolute principle ~ and there are few absolute principles in this world, if any ~ still it contains a very large measure of truth.”

“It, therefore, behoves the popular Government to employ only such agents as will faithfully interpret their will to the people,” he said, “that is, recruit officers and men with a rural mentality in a far greater proportion than hitherto in this predominantly agricultural province. Not only the administration of the province will be carried on in the desired spirit if the rural element in the public services is sufficiently strengthened, but, further, their efficiency will be greatly increased; it will give them a tone, a virility of character as nothing else will. For, a farmer’s son by reason of the surroundings in which he is brought up, possesses strong nerves, an internal stability, a robustness of spirit and a capacity for administration which the son of a nonagriculturist or a town-dweller has no opportunity to cultivate or develop.”

The brilliance of Chaudhary Charan Singh’s writings has been preserved for posterity by his family-members ~ www.charansingh.org is a treasure trove of his life and times. The Bharat Ratna has been bestowed on a worthy son of an agriculturist who owed political allegiances to Dayanand Saraswati and Mahatma Gandhi, participated in Salt Satyagraha, was imprisoned several times, and held public offices for over six decades. His writings, reports and speeches prove that “the forces of nature bring home to the peasant a daily lesson in patience and perseverance, and breeds in him a hardihood and an endurance, i.e. a character, denied to the followers of other pursuits.”

(The writer is a researcher writer on history and heritage issues and former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)

Advertisement